‘Artscientist’ Hopes Sculpture Can Inspire Reef Protection

January 15, 2013

With a blend of science and art, Courtney Mattison is educating people about how global warming, ocean acidification, and other environmental threats are harming the world’s coral reefs.

At first, Courtney Mattison thought she might become a scientist. On rainy weekends during her childhood in San Francisco, she visited science museums and the aquarium, where the fish mesmerized her. While studying abroad in Australia, she conducted fieldwork, surveying corals and counting reef fish species at a research station on the Great Barrier Reef.

But even in high school, when Mattison, on a whim, enrolled in a marine biology and a ceramics class simultaneously, she began exploring the connections between art and science. The easiest way for her to learn the anatomy of marine creatures, she discovered, was to sculpt them.

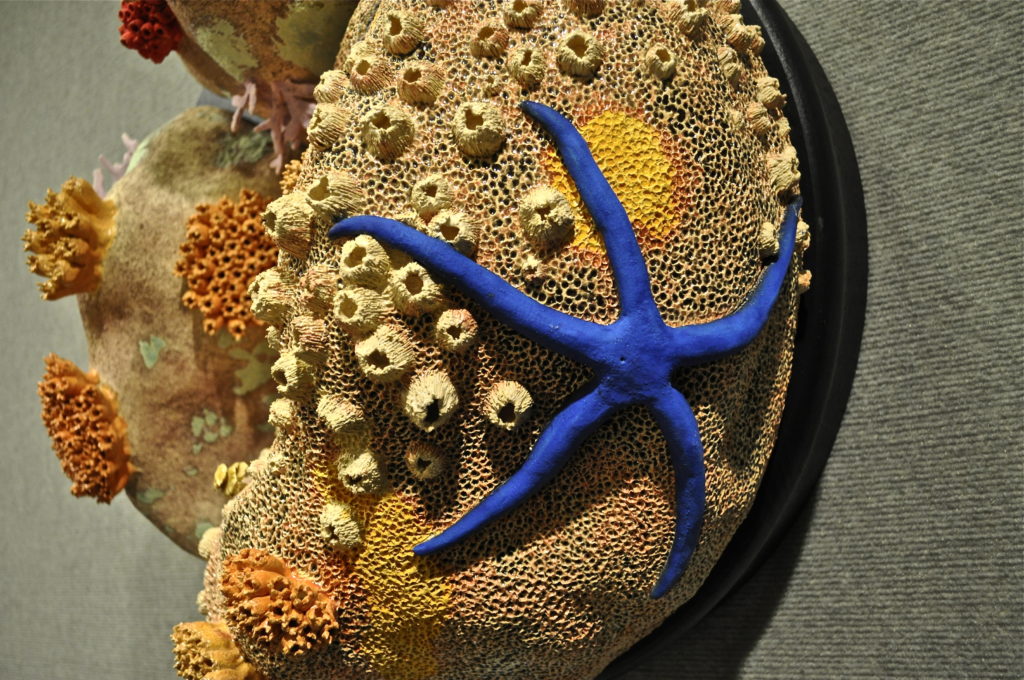

Today, Mattison describes herself as an “artscientist,” a term coined by Harvard engineering professor David Edwards to describe a person who reaches across disciplines, drawing on both the imagination and on analytical skills to address problems or develop new conclusions. Mattison is best known for “Our Changing Seas: A Coral Reef Story,” a 15- by 11-foot, 1,500-pound sculpture that shows a healthy coral reef transforming into a bleached reef smothered in algae. The sculpture, created while she was completing a master’s degree in environmental studies at Brown University, in Providence, R.I., is now on display at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, AAAS, in Washington, D.C.

Connecting Emotionally … to Ocean Acidification

Through her art, Mattison helps viewers understand threats to reefs such as warming waters, ocean acidification, overfishing, and nutrient runoff. “Scientific data can make us understand that the oceans are acidifying, but art can make us connect emotionally to that issue,” she says.

The Yale Forum spoke by phone with Mattison, who is based in Denver. In this edited conversation, she explains the connections between biology and art, how she communicates a sense of hope with her sculptures, and why she hopes her art will inspire people to take action to protect reefs.

The Yale Forum: How did your time studying marine organisms in Australia influence your choice to go into art?

Courtney Mattison: I had seen them in textbooks, and I had sculpted them to the best of my knowledge, but I really hadn’t had much experience actually in the water. The combination of being actually out in the environment, seeing everything for myself and then also taking classes that focused on environmental threats to reefs, and especially climate change and ocean acidification — that really woke me up to the idea.

I realized that I could most uniquely do this combination of art and science to inspire conservation, instead of just strictly being a scientist. I realized that I could, hopefully, develop my skills in art in order to communicate the threats to reefs and other marine ecosystems, in order to get people to become curious about them and then care about reefs, because they’re really out of sight, out of mind. People really don’t think about coral reefs very often day to day.

YF: And so your art puts the reefs in front of people.

Mattison: Right, yeah, bringing them above the surface for people to see. That’s why I like having exhibits in temperate climates or inland, where people don’t necessarily go snorkeling all the time. I’m bringing to the surface little vignettes, or in some cases a large-scale visualization of the coral reefs to give people a sense of hovering over the reef and experiencing it as a scuba diver would.

YF: You have written that biologists and artists have a lot in common. What in particular do you think they have in common, and why do you think they don’t collaborate very much?

Mattison: Well, historically, they really haven’t collaborated a whole lot. I think there’s been such a stigma against that for whatever reason. After the Renaissance, that died for a while.

Artists and scientists really have a lot in common, because they have a shared sense of curiosity about the natural world and really seek to explain what happens in the natural world — and in the world in general. I think artists try to explain things in a more stimulating, creative way, and scientists often just try to state the facts, and it can be very dry. But I do think there is some overlap in there, because artists do sort of do experiments in their work and try to figure out effective methods of communicating and also new ways of seeing the world.

YF: How did you go about creating “Our Changing Seas: A Coral Reef Story”?

Mattison: When I decided to start working on it, I began interviewing some faculty at Brown, and then did a lot of social-science style interviewing of leading scientists and artists who were inspired by nature. I asked them all if art has the potential to inspire coral reef conservation, and a lot of them laughed at that idea, and a lot of them were inspired by it but didn’t quite know what to think.

Artscientist Courtney Mattison often takes dive trips to coral reefs before she begins sculpting them. Photo courtesy of Courtney Mattison.

Only 13 percent of artists believed that art could actually cause people to act to conserve coral reefs, and scientists — I think it was something like 60 percent of marine researchers thought there was a potential for art to actually galvanize conservation action. But I think part of that might have been some scientists just thinking that any form of communication beyond general science papers and graphs would probably be more exciting to people.

Another main trend was that the idea of “doom and gloom” and “there’s no hope for tomorrow” was really not going to be effective. You really need to convey a sense of hope if you’re going to inspire people to actually change their lifestyle choices and act to conserve reefs.

I knew I wanted to show a transition from healthy to degraded reef, because I felt like that was a simple, symbolic way of showing both sides of the beauty and the horror of what’s happening to reefs now and sort of the state that they’re in.

YF: And were you able to give a sense of hope in the piece that you did?

Mattison: If you look at the general layout, I put the really living, colorful, vivid, healthy reef at eye-level, at the bottom of the piece. The piece is about 15 feet tall and 11 feet wide, so eye-level goes up to about six feet. Then there’s a diagonal slant up towards the right where it gradually turns into a bleached reef; and then above that, an algal-dominated reef that’s just smothered in this slimy green-brown algae.

The bleached reef is supposed to convey the idea of climate change and, indirectly, ocean acidification. CO2 emissions are significantly affecting reefs, and that’s the most significant threat to coral reefs today, in addition to overfishing and nutrient pollution, which I was hoping to convey in the algal-dominated reef. When reefs suffer from overfishing and nutrient pollution, a lot of the herbivorous fish [that] are fished out are the ones that would normally be grazing on algae. Also, nutrient pollution causes algal blooms, and so that smothers the reef.

But in the top-right corner, I put a red coral branching out of the slime, as a sense of hope for recovery and the idea that there’s still hope for reefs to recover, even after all of this terrible stuff has happened.

Planting the ‘First Seed in the Brain’ through Art

YF: Why do you think the artists you interviewed were skeptical that art could inspire change?

Mattison: You know, a lot of them said that they thought art had the potential to inspire conservation, and then when I actually asked directly about art being able to change people’s lifestyle choices, that’s where they were skeptical. So I think they know that art can change the way you think about the world, and make you see coral reefs in a new way, and understand a bit about the threats they face, but I think they might have had a sense of viewers being apathetic about actually changing what they do.

“Our Changing Seas: A Coral Reef Story,” by Courtney Mattison, shows a coral reef in transition from health (at bottom) to bleaching and degradation. Photo: Derek Parks/NOAA.

I mean, if you go to a museum and you see something about rain forests being cut down, you’ll care more, but you might not necessarily act on it.

So I feel like creating art that talks about the fragile beauty of marine ecosystems and also the threats they face can be that first seed planted in your brain. That can be a catalyst for people to become more curious about reefs and eventually come to the idea that they’re actually really important. It’s an indirect way of doing it, but it’s a way of communicating the issues that is exciting for people, and potentially new and different that can actually get people to care a little bit more.

YF: What process do you go through to make sure your pieces are scientifically accurate, or is that something you try to do?

Mattison: I walk a fine line with that, because I don’t want to just make dioramas. I don’t want it to be exactly, perfectly, anatomically correct because that’s not always exactly the point. And it varies for different projects, like the one I’m working on right now [for Nova Southeastern University’s Center of Excellence for Coral Reef Ecosystems Research], I’m trying to be a little bit more accurate. I’m trying to actually show distinct species, and at least have it taxonomically legible, because it’s going to be in a scientific institution.

But for me, I just try to think about what inspired me to care about reefs the most and want to save them, so maybe I can convey that to other people. And for me — seeing a coral reef and experiencing that really strange beauty and these forms that are so alien and bizarre — emphasizing that almost-exotic factor in the reef can be really exciting to people that don’t necessarily see reefs all the time.

YF: Do you work from photographs?

Mattison: I take photographs. I try to visit the places before I sculpt big installations. I got to do two dive trips just last year, one in Florida and one in the Caribbean. But for some of the pieces I’ve made, it’s hard to get there. I just have to look at a lot of photos, and a lot of the scientists that I know have published books on different reef ecosystems, and so I can always call them up and ask what certain species are and what color they really are.

Lesson Learned: People Don’t Care if They Don’t Know

YF: From what you’ve learned about communicating about climate change in this way, do you have advice for scientists or other communicators who are hoping to inspire the public?

Mattison: I think the biggest thing I’ve learned is just that you don’t care if you don’t know. And I know a lot of scientists already say that, but if you understand what climate change is through the ecosystems or the organisms that it’s impacting, that can really get people to care a lot more about how climate change relates to the things they love. People are really going to get scared or get angry enough to act to change their lifestyle and stop driving gas-guzzling cars and turn off the lights, and do all these things that can help mitigate climate change — I think that will happen if they understand how it relates to them personally.

That can happen in many different ways. And the one that I’m focusing on is through appreciating the beauty and just the value of nature as it is. Scientists and communicators should really just do a little soul-searching and figure out what they can uniquely do to really inspire people personally to care about the effects of climate change and how to mitigate those effects, because I think everyone has a different talent in that respect.

How to See Mattison’s Work

“Our Changing Seas: A Coral Reef Story” is on loan at the AAAS Art of Science & Technology Gallery, 12th and H Streets, N.W., in Washington, D.C.

Mattison is at work on a new coral-themed installation, to be completed in early February, for Nova Southeastern University’s Center of Excellence for Coral Reef Ecosystems Research in Hollywood, Fla.

Originally published in The Yale Forum for Climate Change, photographs supplemented by Mission Blue.

Visit Courtney Mattison’s website at Our Changing Seas