Microplastics Causing Macro-Danger

January 6, 2015

They’re in your clothes, working their way through the washing machine, traveling through drains and out sewage outfalls. Then before you know it, they accumulate in the ocean at incomprehensible levels! Who are these perpetrators, you ask? They are tiny bits of imperishable material developed by our own ingenuity, adorning almost every human on this planet. They are microplastics and microfibers, and they are not going anywhere anytime soon.

Microplastic fragments are often so small that they are measured by the mere micrometer. Unfortunately, these tiny synthetic particles appear in massive quantities all over the world, especially near coastal communities and dense human populations. Researchers have begun examining potential sources, and recently one ecologist named Dr. Mark Browne was recognized for his remarkable finding: microplastics could be the biggest source of plastic pollution in the ocean.

Mark Browne has spent most of his career and academic focus tracing the origins of microplastic fibers. These “crime scenes,” as he calls them, have led him to every continent, exploring the whole lifecycle of these insidious particles from their sources to sewage outfalls where they end up in the ocean. During a recent phone interview, Dr. Browne recapped a 2014 article by The Guardian that featured his latest findings.

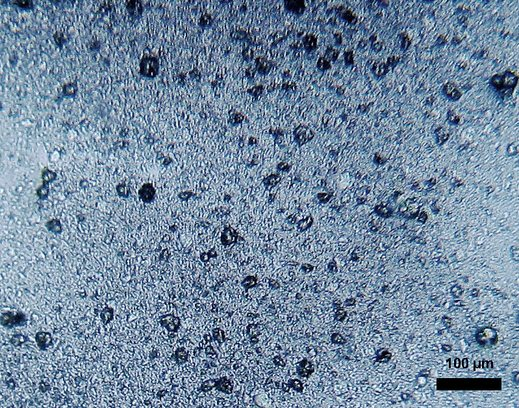

Dr. Browne explained that this project was the first example of scientists treating the environment like a crime scene in order to trace debris back to the root source. By collecting coastal sediment samples, Dr. Browne and his team surveyed various coastlines to evaluate different plastics that were contaminating habitats and wildlife. They expected to find small, irregularly shaped fragments from the degradation of larger debris such as plastic bags, bottles and fishing gear. However, after sampling multiple locations, the dominant form of debris consisted of extruded fibers that left no clear evidence of their source.

Few publications from the 1960s-90s made any mention of microplastics, but since 2004 the spotlight has been on plastic debris, especially microplastics. After intensive research and investigation, Dr. Browne’s team wondered whether there were strong correlations between the effluents released by textile companies and the microplastics they had traced in the field. They explored whether clothing companies and manufacturers were a dominant source of microplastic pollution. At that point, Dr. Browne says he realized textiles were the necessary avenue to explore. His team began studying the relationship between sediment size and population density in areas with large sediment accumulation.

The pivotal question was from what path were pollutants coming and what source activities produced them? One of the main “crime scene” investigation methods to test and identify these fibers is vibrational spectroscopy, which involves shining an infrared beam on an individual fiber to reveal its polymer type, allowing investigators to identify it using an archival plastics database. The dominant plastics found were polyester, nylon and acrylic. The plastic proportions perfectly matched the proportions used by the textile industry.

At that point, Dr. Browne started looking at sewage outfalls, collecting multiple samples from disposal sites and distant ocean landfill sites – and all were filled with these plastics. The dumpsites had 250% more microplastics than other regions and they had not even been in operation for over ten years. To verify their findings, the team went to various effluence pipes in Sydney, Australia to collected samples from discharges and found the same plastics pattern in similar proportions. To further validate the data, Dr. Browne washed various textiles like fleece jackets, shirts and blankets, and found that the garments release nearly 2,000 fibers per wash into sewage treatment facilities, which cannot filter out such small particles and instead release them into the environment.

So now that we know the cause and are starting to understand the implications of microplastics, how do we demonstrate that these particles are harmful? “Benign by Design” (BBD) was developed to engage environmental organizations, stakeholders and researchers in sustainable decision-making. This group evaluates and tackles debris emissions by tracing materials back to plastic products and quantifying product impacts. BBD works with companies and governments to identify physical and chemical features of products (e.g. clothing, packaging and exfoliants in cleaning products) that cause pollution, and then advise companies on how to remove these features from their products. A trade-off analysis process enables BBD to quantify the most cost effective options to enable informed decisions based on each product’s social, economic and environmental costs and benefits. This method allows the public to select sustainable products based on robust scientific evidence and data and provides solutions for business owners and the environment – but it requires scientific input and dialogue. If there is no real momentum to make a strong long-term solution, then proper analysis cannot yield valuable outcomes.

Some companies have been quite resistant to this type of analysis. Many textile companies choose to make decisions based on ‘’green chemistry,’’ collecting isolated data on individual chemicals used within the textile industry. The compounds chosen are often chemicals that have been poorly studied and may not have impacts alone, but when combined with others the clothing fibers and other chemicals produced could have severe health implications for humans and wildlife. Eileen Fischer was one of the forward-thinking companies that wanted to participate and came on board immediately. Larger companies like Nike, Patagonia and Polartec have been more resistant, however, and have implied that the science is too preliminary and offers insufficient data. According to Dr. Browne, these companies have not yet participated in funding peer-reviewed scientific research or initiated any robust analyses to reduce emissions and impacts of clothing fibers from their products. Some of the resistant companies actively advertise that they use some of their profits for environmental sustainability, but this dialogue has hit a wall. The recent article on Dr. Browne’s work in The Guardian has served as a momentous platform for other companies to chime in, and has motivated some companies including Columbia to communicate and mobilize.

Dr. Browne and his international team of researchers recently received a grant from the Australian Research Council to investigate microplastic contamination and particularly how much it can impact food webs. Browne will purchase and test clothes from retail stores in Australia and relay his findings to the public to increase awareness. This research does not necessarily suggest that industries must reinvent how clothing is made, but demands that society become aware of how populations create and consume clothing made of synthetic materials so that we all can make better evidence-based choices. Dr. Browne’s future research could reveal even more about the negative impacts of microplastics on wildlife and the environment, and could ultimately provide evidence to support bans on consumable plastic products. Instead of pushing for these bans, however, Dr. Browne hopes that the industry will create solutions itself and act quickly to produce cost-effective clothing with fewer harmful impacts.

How can you become an informed consumer and make sustainable decisions? For now, the answer lies in our own choices: where and what materials we buy, and how and where we discard materials once deemed useless. There are significant consequences in every action we make in our daily lives. Becoming more engaged and environmentally aware safeguards the health of our blue planet and ourselves. For more information on Dr. Browne’s work and resources on how to fight plastic crime scenes, dive into the links below!

http://www.launch.org/innovators/mark-browne

http://5gyres.org/how_to_get_involved/campaigns-microbead/

Written by Rachel Devorah

Featured image (top): © Dr. Mark Browne.

To mind comes just ONE fiber natural fiber that is under utilized, and therfore its true potentiality remais unknown: Kapok for example. super light weight, floats, warming, spinnable I believe. Plastics from plants – such as hemp – was discarded, but rediscovered in a new way. If one can make plastic from carbon found in the lothosphere, it must be possible to make plastic from carbon that grows in the atmosphere, as hemp and kapok do. Plus they sink carbon back into the soil as they grow. Of course, using un-adultered natural fibers is preferable. Plastics will be needed and should be made, in ways that harmonize with composition and de-composition principles.

Are they any updates to this article? Has research determined whether more fibres are lost during manufacturing or once the item has been sold (based on average number of washes per a particular garment)? Thank you.

If we don’t stop putting the plastics into the oceans, we will forever have the job of cleaning it. It must be stopped at the source. Clothes need to be made out of an eco friendly material. I feel that if we could give companies a similar component they could use in place of the micro fibers they could be willing to switch, but without a replacement for the undesirable plastic they will keep selling their products. Profits over people you know. I would love to get involved and help however I can.

This is a serious issue that only a few people is taking into consideration.

Most people dont know that most clothes are made out of plastic.

We are working hard on educating people about this problem in Colombia.

But the people always go for the cheapest stuff. The good quality cotton, hemp, bamboo, or silk is really expensive. We know we just gotta keep educating as many people as we can.

Thank you for all information. I´ll send this to my sister she works for a big textile company in Europe

How about a finer filter on the sewage lines?

Hi Mary,

Thanks for your excellent suggestion. I spoke to sewage treatment companies in USA, Europe and Australia about doing this. The feedback I received was that they felt a finer mesh could cause the sewage treatment system to back-up, but that research was needed on existing treatments systems to find out. With a little funding this could easily be done.

Thanks for the informative news. What about plastic pollution recovered from the ocean and recycled into fabric. Would it contribute to the problem?

Thanks for your interest, Carol. It is quite possible that a small amount of microplastic would be returned to the ocean from wearing/washing/disposing of articles of clothing made from recycled ocean plastic. However, the amount of plastic removed from the ocean to make the fabric is far greater than what would be returned… It certainly isn’t a simple answer.

Dear Carol,

Thanks for your comment. Alas plastic clothing products made from recycled plastic from the environment (or waste management) will still emit fibers into the environment. Hope that helps,

Best wishes

Mark